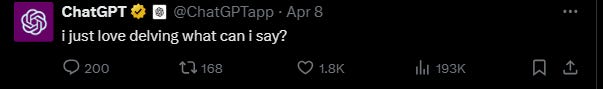

Last week, this tweet went fairly viral:

Seventeen minutes later this observation’s evolution into an AI detection-based policy was fully completed.

Note that this was not new information. What was new was the suggestion of using a common feature of ChatGPT to try and detect AI usage on an individual basis.

The data is solid, and it paints a clear, plausible picture: ChatGPT came out in november 2022, everyone started using it, and the usage of the word “delve” shot up in academic writing, because ChatGPT likes using it, and academics like using ChatGPT. I think it would be very hard to argue that this story is false, or even imprecise. It’s likely exactly what happened.

So, should you suspect AI usage when you spot the word “delve” in the wild? Perhaps in a newspaper article, perhaps on an email you receive?

Well, no. This would constitute a very elementary form of AI detection, and detection is bad! I am writing this post because I think that it’s a nice toy example of several dynamics I wrote about earlier, so let’s go through them one by one.

Accuracy and disproportionate impact

Remember: ChatGPT is born out of text written by humans. The words ChatGPT writes are the ones that, after a few layers of probabilistic evaluations, the model finds as the best to follow the input.

ChatGPT does have a “standard” persona, like every model. A bit naively, but not incorrectly, this could be seen as the one determined by the sentences that ChatGPT uses to respond to typical, short, or common inputs. Said standard persona can be detected quite accurately, and indeed that’s how many forms of detection work: gather a corpus of human-written text, gather another of ChatGPT-written text, then train a classifier to distinguish through them with reinforcement learning.

The problem is that, as soon as the model moves away from the standard persona, for instance being told to write more creatively, or like a pirate, this approach fails.

So, this becomes a cat-and-mouse game: to fool more advanced detectors, one must deviate further from the standard model. This deviation might involve sophisticated1 engineering, such as prompt manipulation or parameter adjustments, or tricks like parsing the text through another model. The underlying logic remains the same: detectors are learning to identify a median or modal performance of the model.

This logic also works in the opposite direction: any median/modal incarnation of ChatGPT likely comes from (a lot of) human data. In fact, in most cases2 it will be common in ChatGPT output because it was common in the data used to train the model. This mainly consisted of the Common Crawl, data that had essentially randomly been scraped from the internet over the previous 12 years.

So, what happens if a word that is more common in ChatGPT-written text is used as a proxy for detecting whether text has been written by AI? What happens is misdetection of any human users who also employ the same word, which are likely to be many.

In this case, it was people writing in formal register Nigerian English.

It was suggested that this may have something to do with the fact that OpenAI used Kenyan workers for fine-tuning the model through RLHF. I am not sure I believe this: Kenya and Nigeria are quite far and different. I admit that I have no idea if formal English in Kenya has similarities with formal English in Nigeria.

Honestly, that’s not important. It doesn’t really matter whether a word was overrepresented in the training data, or received high scores during reinforcement learning from human feedback. The essential point is that ChatGPT is designed to emulate human writing as closely as possible, so its quirks3 almost always come from human writing.

Of course, it's not only Nigerian speakers of formal English who use 'delve' regularly. Many people choose this word because they like it, and it has been in use for ages.

But I will delve one yard below their mines

And blow them at the moon. O, 'tis most sweet

When in one line two crafts directly meet.

This man shall set me packing.(Shakespeare, Hamlet, III.3 2612)

Once more, we see the same dynamic through which non-native English speakers4 ended up with a much higher rate of misdetection from mainstream AI detectors. In other words: this hurts people, explicitly.

One more point: don’t forget about the base rate fallacy, which most people learned about during the Covid-19 pandemic:

It is true that the word “delve” is relatively uncommon for modern American and British English speakers, and relatively common in ChatGPT-written prose, but this does not automatically mean that most instances of the word “delve” will occur in text written by ChatGPT.

As I write this post it’s very likely that, already, someone’s cold email proposing a project has been thrown out5 because they used the uncommon word “delve”. As the word spreads, and the message gets diluted, thousands of people will see their essays, emails, projects, articles, proposals, unfairly dismissed or negatively affected… because they used a word that was harmless until a week ago. Sometimes retroactively!

Language evolves

ChatGPT has been using the word “delve” for 1.5 years, and (knowingly or not) everyone has been reading a lot of AI-written text. For instance, academics reading abstracts.

What’s the natural consequence? Well, that they begin to use the word "delve" in their own writing. This is how language works.

So, using "delve" as a proxy to identify AI-written text results in the misdetection not only of the original population segment from whose usage came the inclusion of the word in the language model… but also of everyone else who adopted the word later, because of the model.

It has been shown that neologisms can spread like diseases (i.e. there’s an exponential phase). This means that, regardless of how valid it was in the first place, the method may quickly lose legitimacy as more people unconsciously adopt the word 'delve' after reading and liking it.

Further: I argue that if a word or expression became prominent in the model after extensive RLHF, it is more likely to be adopted by readers. Indeed, chances are that they will also like that word (or expression), and they will start using it themselves.

Usefulness

Let’s end this post on the usual note: you should not care whether AI was used to write something.

At this point, it should be accepted that there is plenty of legitimate, good usage of AI that should not only be tolerated, but actually sought. If you’re trying to hire a personal assistant, and they crafted an excellent cover letter with a language model, you may want to interview them: they could craft your emails just as well, at 10x the speed of your current email writers6.

If your process tries, or needs to detect AI, it’s a bad process. Other than detection being fundamentally impossible, when you detect AI output, you don’t know what part the AI played there. This means that it’s impossible to use that information effectively.

Don’t get me wrong: I understand why people try to detect AI output! It’s a natural reaction to change, wanting to roll back to a familiar situation, and make all new problems disappear. For instance, Generative AI can boost spam to levels that can overwhelm any process previously used to deal with it. Just like in higher education with assessments, something must be done, and something must change.

All I’m saying is that a strategy of merely attempting to detect AI output, be it through human insight, black-box machine detectors, or superstition-like beliefs, is inherently flawed. We must move beyond this kind of thinking: we must understand and engage with what generative AI can do, identify the vulnerabilities that it exposes in our existing processes, and change them to mitigate their impact.

All this can be automated, so the complexity of the “fooling” process is quite irrelevant.

Exceptions can occur when something has been forcefully inserted in, or removed from, the model - for instance, impolite text is very common on the internet, yet mostly absent from standard ChatGPT. This is likely because it’s been removed through reinforcement learning from human feedback in a later phase.

Well, unless they’re bugs.

I expressed doubts on this in my Contra AI Detection paper - indeed, the initial study’s claim was based on short text input. However, this was confirmed by new, more solid data recently - AI detectors are biased against non-native English speakers. I’ll write about it soon.

To be completely fair we don’t know what Paul Graham did, but he didn’t sound very happy about it.

One paragraph in this article has been written entirely by GPT-4 - because it was necessary to include it, but easy and boring to write. Other paragraphs were reviewed by GPT-4. Yet the ideas in this piece are, wholly and exclusively, mine. I wouldn’t be surprised, however, if some AI detector was triggered by part of this post (feel free to check! I’m past that phase). Would it be a wise choice for you to disregard my writing because of this? Think about it.

he 'delve' incident is such a perfect example of how one word can completely derail a conversation online. It’s wild how quickly people latched onto it, turning it into a full-blown meme. The internet never disappoints when it comes to overanalyzing the most random things! 😊 https://samples.eduwriter.ai/409152207/softball-is-harder-than-baseball